Dr Alex Zarifis

Collaborative Consumption (CC) and the sharing economy, where consumers do not purchase a product or service, but share it, is growing in popularity. This is due to a trend away from ownership towards experiencing. The first two areas of the economy that this business model disrupted were fare sharing and renting rooms for short periods. Other areas are also influenced but it is unclear which sectors of the economy will be disrupted next. Smaller niches of the economy, or areas where more public-sector involvement is necessary, such as the elderly and the disabled may not be at the forefront and may be the laggards losing out on possible benefits for years.

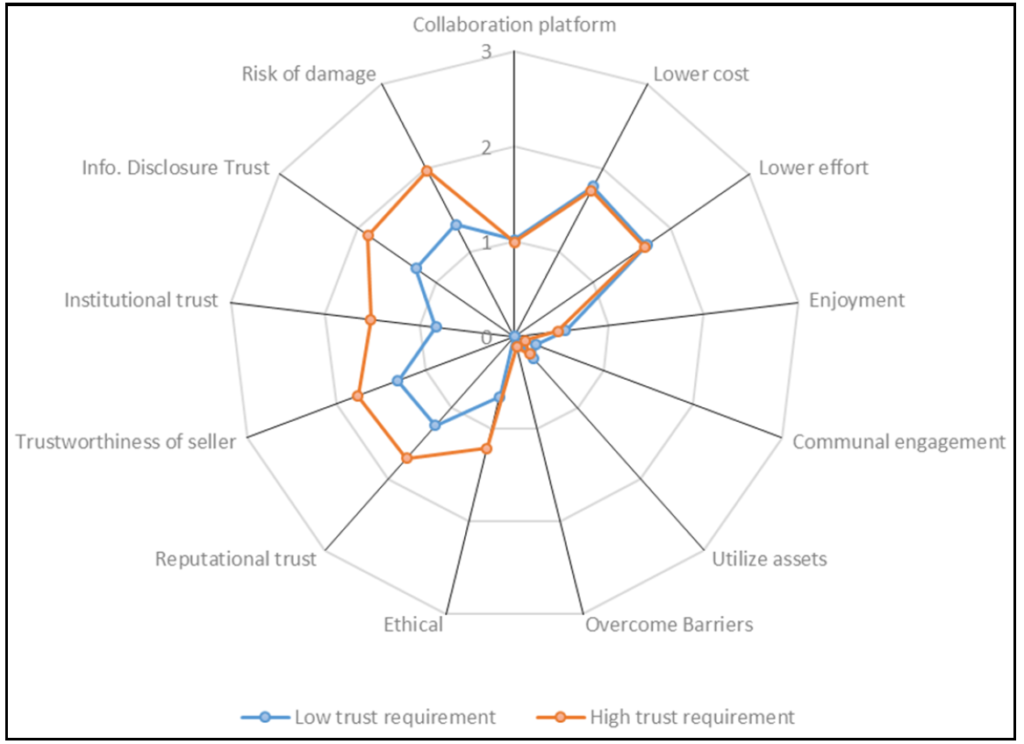

This research evaluates the current CC business models and identifies 13 ways they add value from the consumer’s perspective. This research further explores whether CC business models fall into two categories in terms of what the consumer values. In the first category, they require a low level of trust while in the second category a higher level of trust is necessary. Our survey evaluates whether there was a difference between CC business models that require a low level of trust such as a taxi service and those that required a high level of trust such as supporting the elderly and disabled.

Figure 1. Comparative spider diagram of value added by collaborative consumption business models for low and high required trust

The analysis verified that the consumer requires 13 types of value added from the business model which can be separated into three categories which are personal interest, communal interest and trust building. It is important for organizations to acknowledge how they relate to these dimensions.

It was found that CC business models can be separated into those that require a relatively low level of trust such as fare sharing and those that require a high level of trust such as supporting the elderly and disabled, as we can see in the figure here. For the business models that only require low trust, the consumer considered the personal interest value added more important, while in the those requiring more trust the consumer rated the value added of trust building higher.

The findings suggest that changing CC business model from one that requires low trust to one that requires higher trust necessitates a significant improvement in how the organisation builds trust. This can be considered a ‘step’ change in trust-building which would have to be a consideration at business model level. Iterative improvements at operational level may not increase trust sufficiently.

Reference

Zarifis A., Cheng X. & Kroenung J. (2019). Collaborative consumption for low and high trust requiring business models: From fare sharing to supporting the elderly and disabled, International Journal of Electronic Business, vol.15, no.1, pp.1-20. https://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/abs/10.1504/IJEB.2019.099059 (open access)